Through the Eyes of a Sherpa

Two brown, pixelated faces peer at me from my Skype window, and say hello through nervous grins. A blender whirs in the background, followed by a strange clacking noise; Suren, head honcho of Api Saipal Treks, smirks and apologises for the noise. They’re hunkered down in a restaurant on a busy street in Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, and he warns it may get loud.

I laugh it off, happy to have finally wrangled the interview – it’d taken a few attempts to lock down. Our last scheduled meeting was postponed by a ‘rolling blackout’ that swept across Suren’s neighbourhood. Turns out they’re commonplace in Nepal; calculated power outs see people without power 80 hours a week.

“So let’s get started, Mike!” Suren says, leaning over and angling his phone camera to introduce his friend and employee, Kanchha Sherpa, 27.

Kanchha’s a trekking guide and peak climber – he’d just returned from a recent expedition to Ama Dablam, a 22,493 ft mountain in the Himalayan range of eastern Nepal. His short black hair is scruffy and mussed from a hat. He smiles shyly and tells me in a thick accent that he works on many peaks and mountains: Island, Lobuche and Mera peak and the mountains of Lhakpa Ri and Everest.

I’m curious to learn more about the Sherpa people – they’re the ultimate carriers. Originating from Nepal, they’re renowned for their mountain expertise, hardiness, carrying ability and, some say, miraculous genetic adaptation that allows them to breathe more freely in high altitudes.

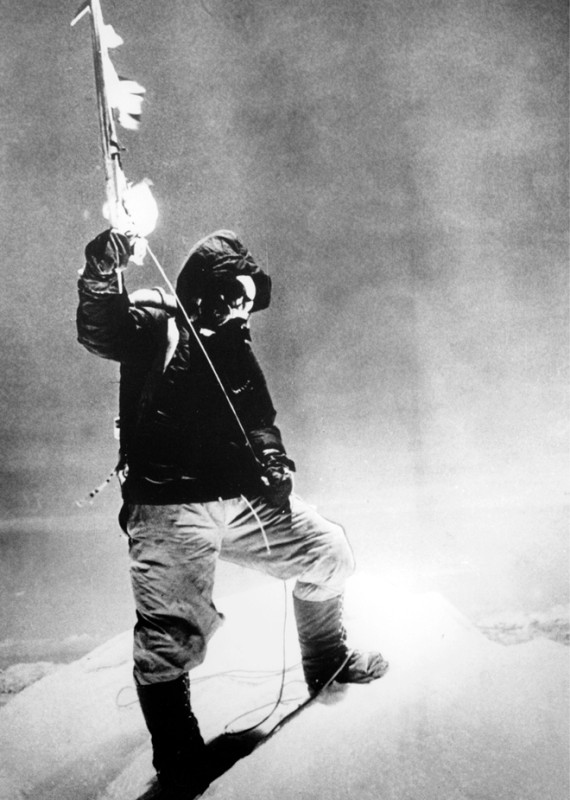

Historically, their fame can be latched to a single moment: the day Sherpa and mountaineer Tenzing Norgay ascended by the side of Sir Edmund Hillary to the summit of Mount Everest in 1953 – an epic accomplishment framed by a single photograph: a bold black and white snap of Tenzing standing proudly atop Everest’s peak posing with his ice axe.

That photograph would shortly after be stamped across the front pages of the world’s newspapers. The ensuing torrent of articles gushing over Tenzing’s bravery and skill undoubtably delivered the Sherpa, in one rad swoop, into mountaineering folklore.

Ever since, Sherpas have been in high demand, sought out by the world’s climbing and mountaineering enthusiasts keen to sweep their pen through a dot-point on their bucket lists.

“I’m very proud,” Kanchha tells me of his heritage, and tries to push his English a little further, with no luck. Suren leans in and translates for his friend.

Kanchha grew up on a farm in Taksindu, a small Sherpa village near Salleri, Solukhumbu District. He remembers his father, Dawa, a trekking guide and peak climber himself, telling tales of adventure to his family over dinner while they sat cross-legged, chins in their hands. He spoke of new friendships, good pay, and the dangers of ascending the mountains that his people praise as gods.

Before each climb a ceremony known as puja is held, Kanchha says, in front of a stone altar adorned with ribbons. It’s officiated by a Buddhist Lama draped in traditional gold and maroon robes. They ask the gods of the mountains for good fortune for the climbing party by offerings of things like cake, yak milk butter, fried dough, fruits, chocolate, and drinks.

The harnesses, crampons, ice axes, and helmets are blessed too, and after chanting and the throwing of rice, the climbers and Sherpa smear gray sampa flour on each others’ faces – a symbol that they may live to meet again when they are old and gray.

When I start to talk about our signature carry geekery, some of it is lost on Kanchha; he seems a little bemused as to why I’d be interested in pack design and brand names. His answers are short and precise.

“A good pack is a comfortable one that is easy to use,” he tells me. When I ask about climbing packs and what he thinks can be improved he says they do most things right, but if he has to point out something it would commonly be the waist belt; “they’re not fitting enough,” he says, but an improvement from the traditional Sherpa packs lugged by his forefathers, he admits. “They were made with a sack, usually found spare in the village, and stitched to rope and slung to the back.”

When packing, he simply stores things he needs last at the bottom (e.g. dinner food), whilst nuts and chocolate are pocketed and chomped down for quick energy on the move, he says.

As a climber, “if you take too longer steps you’ll tire, and if you take too shorter steps you’ll never get there – medium steps at medium pace are best,” he instructs when prompted about climbing techniques. “By keeping steady pace you keep your body from overheating,” he adds. “It’s important to stay cool.”

When quizzed about the ramifications of his job, he mentions his legs always hurt after expeditions. “I sometimes get headaches too from the low temperature and my face skin is burned from the snow,” he confesses, padding his face with his fingers. But with cream and face wash smeared on daily, it’s gone in 8 to 9 days, he assures me.

“And how about your clients?” I ask. “How do they cope? Being untrained and probably somewhat unskilled, traipsing up the slopes? And how do you feel when you look over your shoulder at a client who’s huffing and puffing, while carrying half of what you are?”

Suren translates and they both giggle. “They make me feel lazy,” he says. “I want to slow down too.”

“What kind of loads do you normally haul on expeditions?” I ask.

“Between 15-30 kilos,” he replies.

On occasion, Kanchha admits, he’s even had to carry his clients up the peaks after they’ve turned white and weak-kneed from altitude sickness.

“I’m not only a rescuer but I am a teacher, councillor, porter, doctor and sometimes even a cook,” he says proudly, as the complexities of his work become apparent.

A raucous laugh barks from somewhere in the restaurant and interrupts us. A car horn honks from the street, and Suren and Kanchha lean in and listen carefully. I ask about Sherpa culture and home in on oneupmanship (because it’s something that we Australians love to do). He laughs and admits that there’s always healthy banter between Sherpas: they like to talk up who can climb the fastest, scale the most peaks and last the longest without a gulp from the oxygen tank.

“It doesn’t matter how you look, it’s what’s inside that counts. You have to be fit, to go further and faster,” he says.

And those who excel get fame, he says. And he mentions the Michael Jordan of the Sherpa community – Babu Chiri Sherpa. A legendary mountaineer who reached the summit of Mount Everest ten times (two without oxygen) and made the fastest ascent of Everest, clocking in at a remarkable 16 hours and 56 minutes.

“He died on Everest base camp II,” he says, hanging his head a little. Apparently Chiri had been taking photographs and misjudged his steps, falling into a crevasse.

Even the best, Kanchha highlights, can lose concentration and fall victim to the dangers of Everest. “We all understand the dangers,” Kanchha says solemnly.

His job is dangerous. They expose themselves to the mountains first, by fixing ropes, carrying supplies and making camps for the clients waiting on the ground.

I feel the time’s right and I bring up the recent tragedy that made headlines around the globe: The avalanche of April 18th. It engulfed 30 men, mostly Sherpas; 16 of them died.

It was around 6.30am. The men were fixing ropes on the flank of Everest and preparing the South Col route for international clients. A large chunk of ice (known as a serac) cracked and broke free, triggering an avalanche. Snow and ice came crashing down.

I ask Kanchha if he had any family or friends lost in the accident. He softly nods and says five. He asks me if I’d like to know their names and I nod in turn. He measures his speech:

“Nima Sherpa, Solukhumbu region. Ang Kami Sherpa, Solukhumbu region. Fur Kumba Sherpa, Solukhumbu region. Aas man Tamang, Solukhumbu region and Aasa Gurung, Gorkha region.”

He was on another expedition when it happened and only found out on return to Kathmandu, he says. He was horrified by the vision of the aftermath on a nearby TV. He called base camp immediately for details of those lost and cried when he heard the names.

“Many are still grieving,” he tells me. And since the tragedy, Sherpas walked away from Everest for a long time. Widespread protests swelled the streets of Kathmandu, with members of the climbers’ union demanding upped compensation for the victims and for their members during future treks.

“Some are still unhappy, for the time being the matter is resolved,” Suren tells me, alluding to the fact that the government had finally come to the table and work on the mountains had resumed.

I ask Kanchha if he’s ever personally been in danger, and he admits he hasn’t. He’s both talented and lucky: 200 have died to date trying to conquer Everest.

“Is the pay worth the risk?” I ask.

He says yes, it’s okay. It’s a seasonal thing: six months a year there aren’t any expeditions – the winter snow is too heavy. He works on his family’s farm in his down time, planting potatoes, corn and wheat. He can live a good life, and typically earns around US$125 per climb and up to $5,000 a year. Does that sound like money worth risking your life for? Compare it to Nepal’s average salary of $700 and you might think differently.

“Will you allow your children to work on the mountain?”

“A trekking guide, maybe, yes,” he responds, rubbing a hand through his hair. “But not a peak climber.”

I close with what he’s learned during his career.

“I’ve learned to manage resources properly, to use all the equipment and most importantly the value of life.”

–

*Big thanks to Api Saipal Treks for making this interview possible.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews