Interview with Wookey Design Studio

Creating a backpack company is usually an intentional and carefully considered process. For Sky Sterry and Trisha Wookey it was more of an accident. The couple founded Wookey Backpacks in 1996, a direction they had never intended to pursue when they made their own backcountry skiing pack in order to avoid buying the expensive options on the market at the time. Douglas Davidson delves into the highs and lows of running Wookey Backpacks, and the transition into Wookey Design Studio…

Where did Wookey start? Where did the name come from? What’s the background with Wookey?

Trisha: There’s this artist, Shepard Fairey…

Sky: Yeah. Shepard Fairey. He did the Obey, Andre the Giant thing and Wookey’s Trisha’s last name so actually we’re not riding on the theme of Star Wars but basically we had our own brand for 10 years and ran it under Wookey backpacks. That was the name.

Trisha: But how we came up with that name though is back in college before the Internet. You could buy those underground mags. Five bucks in and get five issues over time. In the college town of Eugene, there were all sorts of underground ones. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of the Dishwasher. He has original Dishwasher mags that he would buy back then, and it was about this guy who toured around the US and was a dishwasher. He didn’t write really well, but it was entertaining. In one of these magazines there was this ad Skylight stickers.

Sky: Yeah. It was basically saying that with five dollars and a self-addressed stamped envelope to Shepard Fairey – and obviously he wasn’t famous back then but he was doing this –

Trisha: You’d get Andre the Giant stickers.

Sky: Yeah. Andre the Giant stickers so I got the thing back and he puts in there this little paragraph about the idea of phenomenology which is – he defined it as the process of letting something manifest itself and it’s kind of like this – put it out there – put something out there and his Andre the Giant campaign was a perfect example. There was no real product. He put this idea out there and it was stickers and t-shirts and I guess that was the product.

Trisha: Because Andre is 7’ 2” most of us were into that weird glam wrestling that wasn’t real but somehow Andre was just this cool guy that everybody kind of knew about but not really. And it was a college project to see – I think Shepard Fairey made the word up. “Phenomenology.” I’m not sure if he made that up or what but – and it said “So this is a college project. I’m trying to see if I can make him famous just by putting this image out here. It’s not a brand, it’s nothing. I just want to see how well we can get him known just from this and like everybody all over the world knows the Andre the Giant stickers to this day and that’s how we stared Wookey. We were like, we’re not going to put backpacks. It’s just going to say Wookey and we’re going to – because not everybody is a Star Wars fan but everybody knows the Wookiee word. And so it was the idea of creating this product that would manifest itself.

Sky: Yeah. And we thought it would create curiosity because what is Wookey? Eventually we added backpacks but we –

Trisha: Yeah. Because people would be like “I don’t know which one I have.”

Sky: We really didn’t want to be associated with Star Wars. We never tried to use that angle in our branding or our catalogues or anything. But it was kind of almost a hazard because we’d send packs to get reviewed at Skiing Magazine and stuff and you’d get the review back. It’d be like “Straight from the planet Hoth. Perfect for your light saber.” And you’re like “No. Other Wookey.” So it’s spelled different from that Star Wars one.

Trisha: I always knew Wookey would just be a good name for a business because it’s Star Wars but yeah. And then the Shepard Fairey Andre the Giant stickers came and we’re like “Oh, that’s even sweeter.” And we knew you could never relate it to Star Wars. You’d get your butt kicked by their lawyers.

But it was my last name. There is also a village of Wookey in England so it’s a solid last name that has existed for a long time.

So transferring over from owning a brand and then being a studio where people have come and worked with you, what was the transition there and why did you decide to change the direction?

Sky: Well, basically we ran that brand for eight years. And we were manufacturing here in Bozeman. We had like a three, four-thousand square foot facility and 10 employees and we’d grown and we had a lot of brand equity that we built up into that and a lot of loyal followers and stuff but the bottom line is we just weren’t making profit. We weren’t making enough money to really thrive. We’d found ourselves that towards the end we were spending all of our time managing and not doing that stuff.

Trisha: We weren’t just managing. We were like the top producing sewers so we were not designing for a living. We were really in a manufacturing business and we were sewing for a living and we had amazing employees, a couple invested in our company. I mean, we had people for years who got paid crap who were just like “We believe in you guys. You work so hard. We want to be part of this.” And so we weren’t good business people. We were growing ourselves broke. The only way we were really able to have people work so hard was we were…we had tendinitis and we were there on the line with them and it made them work hard, but we really needed to move production out of house and have a fixed cost for a pack so it was variable and you had to train people until they started getting fast enough and good enough. We weren’t hitting our numbers to really be profitable. We’d been realizing it from about 2003 to 2005. We were so exhausted. We were just staying still. Basic fast changes to serve just before a show.

“…we’d grown and we had a lot of brand equity that we built up into that and a lot of loyal followers and stuff but the bottom line is we just weren’t making profit.”

Sky: Not doing a whole lot of fresh design work. A retailer would come around and we’d be like “Oh, shit. We need to make some changes or do something interesting.” But just not have the time to put in it. And so we kind of just drew a line in the sand for ourselves. I think we picked basically February ’05 or January ’05 as like, “Look, if we haven’t been able to make this transition from that awkward middle phase of business where things seem really good from the outside, but internally it’s just like you don’t have enough money to really grow the brand…” And we just picked a date and we said if we’re not to point B by this time then we’re just going to pull the plug and we did.

Trisha: And it’s so easy to look back and know exactly where all the mistakes we made were but we started out with – what was it like? 65 and investment. That was like three times we had family and friends invest so we had 65,000 over multiple stock offerings so that many trickled in. And now people are like, “I want to start my own company. What should I do?” I’m like “First of all, you have to have the financing, you have to – you can’t hope that money’s going to be there from Kickstarter.” You know how it is but we didn’t. Ten thousand dollars was a lot to us then, and so in 2005 we said “Okay, we’re looking for investment.” We wanted $300,000 in investment. And there is one of these investment banker groups that we got in touch with and they’re like “Our president owns one of your packs. He’s an avid skier. This is a home run.” And they asked “How much do you want? One million, five million?” We were like “No, no, no, no.” Like we would sell all of our company, we wouldn’t have any control. “We only want $300,000” and they replied “Guys, that’s not an investment for somebody.” They don’t make return on $300,000.

Sky: And plus I don’t make a commission on my half of one percent at the end of the day. He’s like “We need to be talking three to 10 million here.” And us being kids at the time, that scared the pants off us. Three million, that’s a very scary number for somebody who doesn’t have that perspective. And now I mean, we look at that as on shit. I could spend a million dollars in a month.

Trisha: Yeah. I’m like give it to me now. I actually know what I’d do with it now. But back then we didn’t realize you could build a contract a certain way that you do have control over your company but still have investment. We just were too young to know what to do with that money so we didn’t get investment and we just picked a date to shut it down.

Sky: Yeah, we shut it down in ’05 and basically got jobs with Macpac in New Zealand, moved to New Zealand, lived in Christchurch for two and a half years and worked as in-house designers at Macpac which was a really rewarding experience for us because they had that vertical integration of design, development and manufacturing so we had the capability to take our designs and build them in the workshop there in Christchurch. And then they also had in-house manufacturing that was getting shifted to Asia at the time but they retained sewing for 50 people. So it was really a good fit for how we worked, and then the side benefit was it introduced us to the whole world of offshore manufacturing and just how that whole program works with Asian sample rooms. The design process that we have now is stuff that we picked up from our work at Macpac.

Trisha: Macpac taught us a ton. They had really good processes when we first worked with them.

Sky: Because we’re self-taught designers. We didn’t go to design school. I’ve got a bachelor’s in science and chemistry and stuff. And we didn’t know the first thing about running a business when we started Wookey. I had to go down to the library and get books on how to tell – what’s a profit and loss statement, what’s a balance sheet, what’s cash flow, all this stuff. And the same can be said for our design process. We would just come up with ideas that we thought we liked and do it. Whereas now we’re a very process-driven business where we take things through this 15-step thing – initial concept, final concept, counter samples, the whole nine yards. So a lot of that process stuff we picked up at Macpac which was really a good experience. And then in ’08 when the world was falling apart we decided to move back to the US.

“…we’re self-taught designers. We didn’t go to design school.”

Trisha: Well, Macpac was having that really hard transition. They went offshore about when everybody else here went offshore. We’re like one of the last companies that was still making stuff here. We were having a hard time competing with those prices. That was kind of a point where people didn’t feel the importance of Made in America so much. Price was really king and now it’s transitioned. Now we’ve seen it flip all the way back where people care about Made in America again. But basically people were like “Well, that’s great. You’re Made in America but I can get an Osprey that’s less.”

Sky: People go with their dollars and it’s really hard to wave that flag sometimes.

Trisha: It’s funny though. When we first started out we were just going to – it started when we came here. Sky was just going here for one winter to ski Big Sky. It had the most vertical feet. It was the year of the tram and I was a fifth year junior in jewelry school, and I’m like “Why am I going to university to learn jewelry? I should just learn from an actual jeweler. I’m wasting my money here.” And I had actually worked in an earring manufacturing place through college so I really did understand manufacturing and how it worked. And I’ve been on my own since I was 15 so I’ve gotten to see how businesses don’t get run well and as I was like “Man, I want my own business. I can’t take how people – all the mistakes they make.” And so I always knew I wanted a business but I didn’t know when or where that would happen. And we were at Big Sky and it was totally different skiing. And it really helped to have a pack that you could attach your skis to and we were poor as crap, and so Sky was like “There’s this guy who makes Outa Ware.” He still makes it to this day. And he was really inspirational. We thought he was just super cool and so Sky went and bought some fabric from him. We got butcher paper from the cafeteria at Big Sky and I had taught him how to make a stuff sack so I taught him how to sew and he was like “I’m not going to pay you.” So the original shovel packs that were out there were life-length which was basically a rectangular piece of fabric sewn together, and it had some sort of a zipper and then two pieces of webbing and some really rudimentary straps for 120 bucks and Sky was like “Screw this. I’m not going to spend $120 on this thing. I can make something better.”

Sky: This is where Wookey started.

Trisha: And this is original.

Sky: So basically back then you could buy a Life-Link backpack that was – it was rectangle. And so I built that and so many people were like “Man, you can see how choppy that is.”

Trisha: Yeah. And you get to see how crude that is now but people would stop him on the hill and so –

Sky: And then this is kind of one of the later evolutions of that idea which is basically a really high riding ski pack.

Trisha: It was just set up high so when you’re sitting on the lift it didn’t want to push you off. It doesn’t hold a whole lot. It’s just for day use skiers.

Sky: And it’s got this kind of unique wrap-around design that was unique at the time but you see a lot of this now.

Trisha: It’s all like side-release buckles if you need to just drop that thing really fast and get it off for an avalanche, you just click it all off. So it’s kind of military style with the side-release buckles, and when we first started doing this you could customize your packs. We realized people really wanted their custom colors so there’s a panel, there’s a metal strip and then there’s a main part. So they can pick out those three colors. And then we also had just put together random colors. So the original Wookey packs, you can spot one in a second because it’s just hideous color combinations.

Sky: That would be really popular now again because of weird colors.

Trisha: Oh, yeah. Because Andy Tuller, the Outa Ware guy, it probably more came from Andy because you go into his shop and you could customize your colors and way later on I was giving him shit about his coloring and it turns out he’s colorblind. And I’m like “Oh, that explains everything.” But people would still wear them and so maybe that’s where it came from or we just realized that was just such a big hit with people. They felt like it was even more theirs and they could pick out a color. We had the sewing machine in the corner of our teeny little living room. I don’t know where we even cut stuff out. It must’ve been on the kitchen table or something but we would cut stuff out and sew up stuff originally in the living room and then it moved out to the garage of our house. Our house is 720 square feet and the garage is 900 square feet. So that was our original factory.

Sky: It was like the classic born-in-the-garage story. We had this huge garage which was awesome.

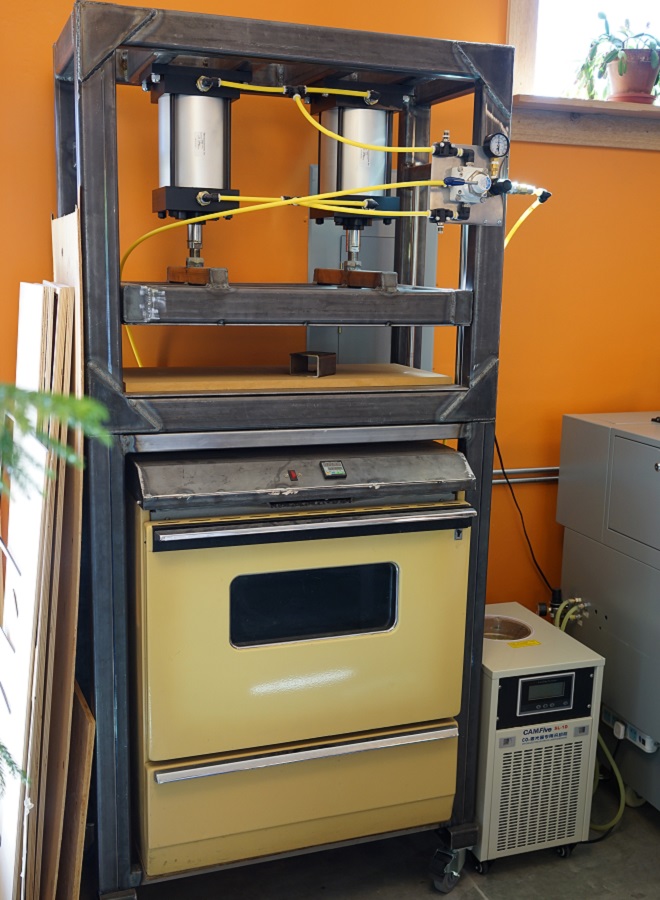

Trisha: It was wood heated. Another thing about this pack, what was so unique is it’s – I mean, this is a really old pack and it’s still holding shape but we laminated two layers.

Sky: There is a plastic laminate between the two layers in the shoulder space.

Trisha: Yeah. So you know how you always see the shoulder harness break on packs? So we would take two layers of foam, laminate plastic into here so it wouldn’t break, and then we added another layer of foam on top of that. But you can’t really legally get people to do that – so we’d wait until everybody was gone for the day. We would put on masks, we’d get the fire stoked, and then open up all the doors and laminate till 12 o’clock at night.

Sky: We actually did have retailers call us and be like “I opened up the box of packs you sent and it smelt like wood smoke.” Because we heated the whole workshop with a wood stove.

Trisha: You had to get up at six in the morning.

Sky: And so I’d have to get out there at six in the morning, stoke it up then make sure it was really warm on time. It gets really cold in here. So it’d be warm by the time sewers would show up at eight o’clock.

Trisha: And it was totally – oh, my god. People would’ve shut us – I mean, you literally had to squeeze by each other in the aisles and we didn’t have great ventilation for cutting web and it was super ghetto. We had no money and it looked like something out of Vietnam. I have the old ladies all bundled up sewing.

Sky: Those were the early days.

Trisha: So we used to get frustrated. We just sold locally and we would sew up these weird combinations and then we would bring it around to our five stores that were within a drivable area for a Volkswagen bus and we would open each box; pull it all out of the bus, open each box and then the retailer would pick the colors he wanted and then he had this little catalogue with 13 colors. We had these little color booklets with the fabric colors and if they had a special order from a customer then they would place their order. You needed somebody just to do the orders and all that. That was a lot of work because they always wanted – you had to put all the boxes out, he had to look at each color and you’re like “Can we just randomly pick five boxes?” So yeah. We shut down the color thing after probably our second year because it was just really time-consuming.

Sky: Yeah. It was a nightmare. We would cut out huge stacks of all the panels just in all the different colors but then you’d inevitably end up at the end of the season with a bunch of stuff, the unpopular color and that’s hundreds of dollars if not thousands of dollars’ worth of stuff you’ve got to throw away at that point or build into stuff that somebody doesn’t want. But yeah. Those were kind of the early days.

Fast-forwarding to today, you’re obviously in a totally different scenario. But looking at you versus other design studios out there, and we know you don’t necessarily just call yourselves a design studio but in this field for packs, carrying solutions, camping, each outfit has their own specialty. What do you think makes you different or what do you think gives you a little bit more value in the context of working with you?

Sky: There’s a lot of great designers out there and a lot of people who can draw great-looking design, great-looking packs and I think that our ability to build the prototypes in-house here and not only build the prototypes but also inform our design process with our knowledge of building the prototypes and our history of manufacturing and designing towards manufacturability is really a value-added thing for us because a lot of people will design packs that a manufacturer will look at and be like “Well, you simply can’t sew this that way. Impossible.”

Trisha: Those seams don’t go together that way.

Sky: Yeah. So I think that that definitely helps, and our clients will tell us if they save time by coming to us because we’ll cut their sample turnover. They’ll take a design to Asia and it’ll take them 15 days to get it to the point where they really like it.

Trisha: Depending on who the manufacturer is.

Sky: Yeah. Right. But we can really cut down that amount of time for people.

“…our knowledge of building the prototypes and our history of manufacturing and designing towards manufacturability is really a value-added thing for us…”

Trisha: If you talk to almost all designer developers who have to go to the factories they’re spending a minimum of 10 days over there. A lot of times two weeks. A lot of our customers we don’t even interact with personally. A lot of it is just via email and we have a really big paper trail so you can follow the whole process. We make sure everything’s documented but we’re able to communicate with them differently than Asia; you have that whole time difference thing where you have to wait 12 hours to get your answer back and it’s – even with photographs and all of that stuff their sample rooms are so busy that they don’t really have the time and understanding. These people don’t use the backpacks that we’re making and they don’t really give a crap about what that backpack is supposed to do. They’re just trying to follow a picture and so we actually have that communication. We actually know and understand what the customer is using it for. We’re actually trying to find that unique place in the market that their product is going to stand out, so when we work on a product we’ll do a lot of research about all the competition and say “Okay. What can we do to make that one different from everybody else doing the same product?” And the factory’s not going to do that for them.

That’s a great point. When you think about working with a factory versus working with say somebody like yourselves, a lot of times at the factory level it’s more about efficiency and it’s not necessarily about creativity or trying to do something different. Is that somewhere that you feel is a strength in some ways because you do have the factory and the knowhow but at the same time you’re also creatively thinking about how to reconstruct something versus copying whatever you’re given?

Trisha: Yeah. You’ll be like “Oh, do you have a solution for this?” They’ll go grab somebody else’s bag and say “Let’s do it like this.”

Sky: You see a lot of cut and paste solutions from – and really honestly the sample rooms in Asia end up being these giant cross pollination chambers where they’ll be taking the ideas from their different clients and combining them to a solution for you rather than coming up with a new way of doing it.

Trisha: But they don’t have the time. You see how busy they are. I don’t blame them for what they do. They do a great job for how much they have to do and how many iterations you see them have to do. We have customers that are like “Okay. We like this pack but we want to do five different iterations with different pockets and let’s just see what we like.” And you’re like “Do you realize how much work that is for them? Why don’t you get your designer to draw those five different iterations you’re talking about and try to decide because you just took a ton of the factory’s time to make that.” But people don’t really care about that. It’s an easy way for them to look at things, and they won’t push back like we will. We’ll say “Well, we’re only contracted to do this. Let’s make it and let’s dial that in rather than…” We have to rein in the design at some point whereas the sample rooms, they don’t have that power. They’ll just be like “Okay. We’ll do the five iterations.” And it’ll take a lot longer for it to get done. With us you’re actually paying for that process where there it’s basically free. I mean, they build it into the cost somewhere. But it does get built in there and how long they took to develop something does matter but here you can say “Okay. If we’re going to do five iterations this is going to cost you this much more to do it.” And they’ll say “Oh, okay. Let’s try to design it.” So it helps to narrow the decisions because you can always say something should be better or different or this isn’t quite perfect.

Sky: Yeah. Perfection is impossible. It’s a moving target and I think that a lot of clients that we’ve dealt with don’t understand the whole idea that “Look, it just has to be good enough for right now and that perfection is just an unobtainable goal because what is perfect today will be imperfect tomorrow.” There are always ways to improve something.

Trisha: And there will always be a decision where you hear that it won’t quite fit. There’s always multiple people deciding and you might have three of them on board but the fourth one, they might have a different idea. They might just want one more thing. That’s the thing too. There’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen a lot of times. You kind of have to say “Okay. We’re going to draw a line here. It’s good enough for now. You can put all those things on the next version.”

Seeing where you are at today and let’s say 20 years ago there was only a handful of bag designers and people who worked on bags. Today is a different story but a lot of young designers ask how do you get into bag design…

Sky: Yeah, right. There’s no school.

Trisha: There is something in Seattle though. There is some sort of thing that’s actually teaching something other than apparel. I think it’s a trade school and I can’t remember what it’s called but somewhere in – I think it’s around Seattle.

Sky: I think it’s very apparel focused but you can get like a side of bags, but there really isn’t a school for it. To design a bag and to build it are two really different prospects. I mean, for a young designer to be ambitious enough to say “Hey, I’m going to go get a sewing machine and just start building stuff and let that inform my design process.” That would be a great way to do it but I think that anybody who’s got an imagination can be a bag designer if you cultivate that skill and just do it. Draw lots of pictures and just consume as much outside information as you can and feed it into your process.

“…perfection is just an unobtainable goal because what is perfect today will be imperfect tomorrow. There are always ways to improve something.”

Trisha: They’re normally industrial engineers. Seems like most bag designers that we work with, they went to industrial engineering school and then that was a particular interest that they had. There’s a lot more acceptance of it and you can actually make a living doing it. But it’s probably not encouraged with schools I would imagine. There’s a lot more you can do with your industrial engineering degree.

Sky: Our buddy Ryan Hetzel is a designer at Lowepro. He’s like “You need to start a school. Just start a school.” I’m like “I don’t think I can make enough money if I did that.”

Trisha: Yeah. “Maybe when we’re retired we’ll do that.” If we teach people how to do it they’re going to jump off and start their own things so it’s kind of like this awesome niche where not a lot of people – I mean, I’m so glad that we went the route we did. We had to learn how to do everything, it was painful a lot of times and just a ton of work. But I’m really glad we had that and it almost takes going through those trials and tribulations to understand everything. But there’s got to be a shorter way to do that.

I’m sure there were some points where as a couple you’ve had some interesting times along that route too and how you had to navigate the tensions of working together. But then also those tipping points where it was all of a sudden you were just like “You’re in business.” And you were probably like “Holy shit. How did we get in business?”

Sky: Yeah. It was really kind of accidental. I mean, we built that pack and people started bugging me and you then got 10 people wearing them and then, next thing you know I’m buying thousands of dollars’ worth of – it was really not my intention to start a business when I built this backpack.

Trisha: That was a really big time for us because really Sky went to school for biochemistry and I mean, really he was good in that too and he really had an interest in that. His dad was willing to pay for his further education, he’s a super smart guy and he really would be helping out the world a lot more if he had done that. But we’re making bags for a living. So that was a really hard time to be “Do you dump that?” But after Big Sky we had that bag, we had bought a machine and we’d been screwing around with actually honing the bag but we didn’t really know why. Like “What? Is this a side deal or something?” And we visited his parents that summer and his dad who is an Oregon skier said “If you guys started a company and made that bag I’d invest in it.” And we weren’t really even talking about a company.

It was just kind of this extra way to make money or something because we were both working in restaurants and just those crap jobs that you’re asking yourself “What are we doing with our lives?” And kind of just waiting. He had to do the test that gets you into grad school, so he was boning up for that, taking a few extra classes that would help him remember how to do all the math that’s involved and everything. But it was Sky’s dad saying that that really I think was –

Sky: Yeah. It was a catalyst. It still took him five, six years and it was only like $5000.

Trisha: And it was almost him suggesting that made it okay to make me go that route.

Sky: But really the only crossroads that we ever really had was when we shut the manufacturing business down and I was going to start a concrete counter top business or something. Anything to just make the bills work but we got those jobs at Macpac and then even after we quit when we moved back to the US in December ’08 and the world’s falling apart, we have just been exceptionally fortunate, we just landed design job after design job. We got a big job with BD right away and they were just launching their backpacks. We helped them kind of crack that whole program and it’s just – knock on wood, it’s just been a good roll.

Trisha: And when we came out and when we announced to everyone we were going to do design development pretty much everybody we talked to just laughed at us. They were like “Your portfolio is Wookey. Why would I hire you? All you know how to make are these packs.” So we’re like “No, no. We understand how to make a pack. We can make it however you want it to look. We have that understanding. We don’t want it to have our signature. We can do that.” And people said “No way. You guys have no experience.” And we couldn’t convince people without a portfolio that we could do that and so that was when Macpac said we’ll hire two senior designers at once which was huge. Like trying to get two jobs at the same company in the same place. And then they were willing to move us out there and we had all these crazy things happen. One of our big mistakes was we didn’t have the right investment to start out with and we financed a huge amount of our company on credit cards so when we shut down in 2005 we had $65000 worth of credit card debt that we were paying upwards of 18 percent on. So our payments weren’t even paying after principal. It was just interest on $65000.

Sky: Yeah. You’re spending like three grand a month on credit cards and not going anywhere with them. But we’ve made every payment and we ended up paying it off and basically took it out of the house.

Trisha: But it was owning that one piece of property. Thankfully this guy sold us our house that we live in, owner finance. We decided to put $5000 down and I had a great grandma. She was just awesome and said “If you’re going to do something smart with this money, I’ll give it to you.” And it was that little thing really that helped so much because we were able to take that house, refinance that, we were trying to buy this other property. That fell through. We bought this other piece of property for zero down, had renters in it. It gets paid for by the renters and then we took that $60,000 and paid it off when we probably should’ve just gone bankrupt.

Sky: Your whole supplier network is like your friends at that point. We were in business for eight years and I wasn’t about to screw any of those people over and just say “Hey, sorry guys.”

Trisha: Yeah. And I would call them and be like “I know I owe you 1200 bucks but can I divide that and do three payments?” We’ve always been honorable people. You don’t let anybody down and they helped us out so much and we would – 1200 dollars is a huge amount in buckles that we’d have to buy and they let us divide it into three payments. Those people helped us be where we were. It wasn’t like you were going to just kill all that. So we paid off all of that. Then we had investors and we were like, we don’t know what we’re doing but you guys invested. That would just be the wrong thing, to go bankrupt. In hindsight we should’ve just went bankrupt. It wouldn’t have been a bad thing.

What’s it like to go through a crossroads like that and then come full circle in some ways, being told by somebody “No, you can’t do this.” And all of a sudden now you’re building designs for expeditions.

Trisha: It goes to show you’ve got to prove yourself. You have to have a portfolio. You can’t just say “Yeah, we know,” and expect people to just take your word for it.

Sky: And we knew too. I mean, all we had was Wookey and we talked to all –it’s a small industry as you know. There’s probably 50 companies that we make it our business now to form personal relationships with all design directors in these companies and it’s a very small market for us. Back then we would reach out to all these folks and hear the same thing over and over from these people. Obviously we kind of needed to get a little bit more – and honestly when we shut down Wookey, before we went and worked for Macpac, we really were still greenhorns, self-taught designers.

Trisha: We didn’t think we were then.

Sky: We didn’t have a design process. Even our drawing skills were not – we were only drawing pictures to present to ourselves. We weren’t drawing pictures to present to a sophisticated client. So even those skills at that point in time needed to be developed and we got to Macpac and I’m sketching packs and going “Wow. I’ve got a lot to learn here still.”

Trisha: At the time we thought we were perfectly capable but we always say Wookey was our bachelors, masters and Macpac was our doctoring.

Everybody kind of goes through those points of like “I just blew all this money. I just lost everything.” Then after they kind of rebuild the house. It looks like you guys are in a great spot; what projects are you guys trying to break out of your traditional outdoor space?

Trisha: That’s one of our problems because we’re pattern makers/engineers. A lot of our job is engineering stuff and so a lot of our portfolio is very technical stuff so we really get picked by companies to work on their most technical projects. So it’s hard to say “Oh, we just want to work on a lifestyle bag.” We could make that bag so freaking cool because it’s simpler, we don’t have to spend all this time engineering a harness system and the back panel but people are like “Well, that would be kind of a waste of our money on you. We need to put you on this super technical project because we have designers in-house who can do the daypack.” We’re like “Yeah, but just think with our skills…” So we’re always pushing and we have some cool projects now that are going more lifestyle. We don’t go to the other shows because every time we go to OR we just always pick up – it could be two to three jobs that we pick up each show so we’re like “Wow. It really would be great to go to the biking show. We just need to do that. Or the surfing shows.” That sort of stuff.

That would be one of our weaknesses. It’s like how do you make that move out of outdoor. There’s the whole fashion world which is way more of a money maker but you just have to get out there and let people know you’re out there.

Sky: Yeah. And we really try to wrap our minds around other industries and stuff and if we get a chance go to an automotive manufacturing facility or a footwear facility or a mattress facility or whatever because you never know when those crossroads are going to happen and you’re going to have some A-HA moment from something that you’ve seen. But just like footwear, we’ve always been super interested in footwear and the technology that goes into it and we recently toured a footwear factory and it kind of demystified that whole manufacturing process for us. You’ve seen companies in the past tried to combine footwear technology with bags and putting out soles on bags and stuff like that in a way that doesn’t really work but there’s those crossroads, there’s those moments where I think our technology in backpacks will evolve and start to bring in more of those kind of ideas where you’re doing more gluing and laminating the stuff. One of the things that I feel is holding our entire bag industry back is our reliance on woven material. How long have we been using basically woven nylon for bags? And I think that if things will shift a little bit more towards non-woven materials that could be a real game changer in bag design.

“…we really try to wrap our minds around other industries and stuff and if we get a chance go to an automotive manufacturing facility or a footwear facility or a mattress facility or whatever because you never know when those crossroads are going to happen and you’re going to have some A-HA moment from something that you’ve seen.”

Trisha: The bag industry is so young that we just follow everything else that’s out there. We don’t really innovate. We just take often from footwear, like all of our fabrics are pretty much from footwear. We know they’re durable and that they’re going to work well. That’s one of the weak points of bag design. But you’re seeing it change. We’re starting to mature. We’re like teenagers now.

Are there things that you guys have stumbled across that you kind of kick yourselves from a competitive standpoint, innovations you didn’t fully capitalize on?

Sky: There’s probably stuff like that, if I really dug hard I could probably come up with some examples but I know what you’re talking about. And now with Kickstarter too we get so many people coming to us with everything from totally harebrained ideas to really cool stuff and we’ll see really cool stuff and have to turn down these projects. The guy who started Sunskis is a classic example of “I’m successful, I funded my campaign on Kickstarter. Now what?” It’s like people don’t really have a plan post-Kickstarter what they’re going to do. They’re starting a brand, they’re starting a company and they don’t really have the foresight to say “Okay, once I’m funded then what? Once I ship all my product then what?”

Trisha: How are we going to have sales for a long time? It’s really interesting because we came into the industry before the Internet and before all these ways that you can buy bags and there are a million bags out there. People are always saying “Why don’t you guys start a business again?” And I’m like “Maybe if I ever figure out how you actually sell stuff and know your sales are going to be solid.” How do you market? How does this whole new age of marketing work? It scares the crap out of me. How do you stand out among all those other websites that you can come on to.

Yeah. That’s a good point. Like something in the outdoor industry that I – I’m an outsider to the outdoor industry and coming at and meeting all the different designers and meeting the different design houses that you work with, outside of a couple of people that I’ve worked with everybody’s not really that competitive. Everybody’s like “Hey, just sharing information.”

Trisha: Yeah. This love of this industry and that’s why I’m in it.

Totally. So you get the outsiders, and then you have big firms that have been around for a long time and they’re uber-competitive. So from that space have you ever felt like that’s what kind of holds back the outdoor industry or do you think that’s what kind of keeps it authentic in that context?

Trisha: I think it holds it back.

Sky: Yeah. It’s a very myopic industry. I mean, we’re all drinking the Kool-Aid in the industry but it’s changing. It feels like it’s changing with the whole urbaneering thing and up until just a few years ago the packs were just – everybody’s trying to out-techify each other. I mean, what are we doing here, folks? A lot of it doesn’t make any sense. And so now it really feels like we’re starting to get a little bit more sensibility in design where it just doesn’t have to be the most technical stuff and the urbaneering thing kind of coming in and saying “Hey, there’s fashion here. Let’s talk about doing things different.” Backpacks become your friend. When we were doing this project people would bring their old Wookey packs in and the thing would be beat to hell and completely falling apart and they’d be like “Can you fix it?” We’re like “Let’s just give you a new backpack. That one’s getting more tedious. Take the new one.” “No. I want this one because it’s got my patch on it from Ireland.” And so bags become kind of like these lifelong partners. And I think that if you can create designs with that kind of relationship in mind rather than “Oh, it just needs to have all the latest technical frippery on it,” I think that’s something and I think it’s happening. I think brands are starting to understand that relationship between the bag and the person.

Trisha: But it’s interesting. We’ll see how it goes because almost everybody is owned by a big holding company and those holding companies, all they really care about is making money. Like Black Diamond, the people who bought Black Diamond and Gregory I think originally that group – they were like “Oh, we love the outdoors and we just want to keep it just how it is.” They’ve already sold Gregory because it just must not have been making the money it needed to make that they wanted to see every season. So the bottom line is they really only I assume care about the profits and when it comes down to it they don’t really have that passion that people who are working in it have, so what will that do to it or is it all just going to look like the fashion world. But it’s funny. Remember when outdoor fashion used to be like a four letter word and now we’re seeing fashion come into the outdoor and people really love it. It’s just really interesting. You think it’ll never change and what could we possibly do different but it’s amazing. You see that Herschel old school coming back which I thought we had kind of done that already but now it seems to – I mean, we really seem to be in the middle of it right now. So yeah. It’s really interesting to see what people think is fashionable.

“I think that if things will shift a little bit more towards non-woven materials that could be a real game changer in bag design.”

And back when we started, we came into the outdoor market at a very strange time. When we first started with these little packs this was going to be the one pack that we ever made. We had no plans to make other packs. It was very unique. Nobody did anything like it and we were going to work in the summer and ski in the winter. That was going to be our life. Then we started going outside of Montana and going to other stores and we were like door-to-door selling our packs and they’d be like “Wow. You guys can’t be legitimate. You only have one pack in your line.” And we’re like “Well, everybody has the whole pack market covered. What would we do different? This is the only thing we can see that we would do different.” And that was when we just happened to be there at the right time and be able to identify the hole in the market. This is right when the big huge 90-liter pack backpacking was kind of coming to a stop. And people didn’t have time to do that 90-liter thing, they didn’t have time to do those two-week trips that you used to hear about back when we were kids. So you could sell that 90-liter pack for $400 and you could sell this pack for $120 but really they’re about the same amount of work to build. So nobody wanted to make this pack and only get the small profit when their cost was very close to the same but they could make a huge profit on that big backpacking pack, and we just happened to be there right before the big crash of the big pack market and we saw “Wow. Nobody really makes a technical mid-volume small pack line.” And so that’s where we decided our niche was. “Okay. We’re going to build super bomber, technical daypacks and smaller packs because nobody’s doing it.”

Sky: And really focused on the panel loading designs. I don’t think we had any. I think in the end we had like 3300 to 4500 cubic inches panel loading backpacks. Big panel loaders.

Trisha: Just from when we started we got to see the end of the huge backpacking. I mean, external frames were still selling well. Internal frames were in their heyday, and starting to slow down and then it was like the smaller packs now. Then everybody realized that kind of around the same time and thankfully we got in just a little early so our sales were really good but then that’s the way everything went. And now you get to see everybody’s going from technical to more simple. And if you really talk to everybody almost everybody just wants a no-frills pack. Everybody wants that clean – they don’t want it to weigh a bunch but they just really want that clean look. I don’t talk to many people who say “I want to have daisy chains and lots of buckles and a totally complicated pack.” They don’t want this. We look at this now and think “That bag could be so simplified. Who uses these?”

It’s true. In terms of influences and whether it’s outside influences or influences inside the industry, what’s kept you inspired? What’s kept the fuel in the tank so you don’t end up burning out?

Trisha: Everybody has a bag that is one of the most important things that they have in their possession. Everybody has a backpack or some sort of bag they really love and everybody, no matter who you talk to, everybody has an idea for a bag that they would make. And you would think that it’s all been done and it probably has been but it’s working for – we really do like working for different customers. We really like having long-term customers. That’s a lot cooler to really understand the company you’re working for and get a good working process but having those different projects and thinking about a bag that we wouldn’t normally want to make for the market ourselves but – you have all this different input from different companies and they have a bag that they want made for a certain reason and they feel very strongly about it and they’re all excited. It rubs off on you.

Sky: And I think just being in Montana and getting to interface with the outdoors and then – our vacation is truly our vocation. It’s like I really enjoy coming to work and when we finish up a bag sample and stuff it and take pictures of it before we send it to the client and measure it and do all that stuff it’s just a great feeling of satisfaction to look at that thing that was just a piece of paper earlier in the week and say “Wow. I built this from scratch over the course of a few days.” And that’s just a really satisfying thing to build stuff with your hands. It’s truly a fun job.

Trisha: I think everybody likes building stuff with their hands too. I think even if people think they’re not good at it, when you actually have something you can be like “I made this.” It just feels good.

Sky: It’s the analogy of the builder becoming the architect. And then the architect is still building the house. It’s fun. It’s real fun.

Trisha: Every time you send a bag to a customer and that praise that you get back and everything. I mean, I guess every once and a while somebody’s not completely happy but I don’t think – I can’t think of an instance where that happens because people – we’re just looking at a job we’re trying to get right now and they’re saying “If by March we have an actual – it doesn’t even need to be a functional bag. If it just even looks similar to our drawings.” And I’m like “Dude, by March we’ll be in third iterations. You’ll be able to use the first one.” People’s expectations are so low and then when they actually get to see a real bag that really functions, that looks like the picture – we actually get a lot of that “Wow. It looks just like the picture.”

“…that’s just a really satisfying thing to build stuff with your hands. It’s truly a fun job.”

Sky: Yeah. We saw this with companies a long time ago. There was a couple of products. We thought “Well, gosh that just looks really bad.” And then we would see the original design attempt, the original design drawings and the drawings looked fantastic and we would think “Well, how is that this kind of piece of shit over here?” And so I think there’s that disconnect and like Trish was saying the expectations are pretty low and so being able to kind of beat the expectations, and the sample rooms are kind of building modified cylinders that are not really – we’re really trying to put that kidney bean and the hourglass kind of space beam fastness into our pack designs whereas most companies are building cylinders. There’s a lot of exceptions out there where some are obviously crushing it with bag shapes but yeah…

Trisha: And actually yeah, not just doing the cylinder with panels on it. We’re actually trying to give the shape that the drawing shows and give it the volume where it’s supposed to have the volume. It’s seldom that you find a sample room pattern maker that actually does see that in the drawing and actually tries to get that.

Sky: Yeah. But the limitations are it’s never ours. It’s like you’re still designing something that is not how you would do it if you were doing it for yourself because you’re doing it for the client and they have their own set of expectations, their own needs and their own brand identity that you’ve got to design into and that’s always a challenge, especially if it’s a new client. The ultimate satisfaction would be having your own brand and controlling everything and doing it exactly how you want to do it and it’s so tempting. With Kickstarter now – we’ve had this discussion so many times and we say “We really should Kickstart some – or just start a brand. We can crush it.” But then we’re so happy doing what we do now that it’s like if it ain’t broke don’t fix it. Maybe down the road when I’m an old crusty designer who nobody will hire, I’ll start my own branding.

Trisha: We do have to worry about sales because people won’t keep us around if what we design doesn’t sell but it’s also nice being removed from all those meetings that internal people are in about the sales and the sales people always have different expectations than the design people. Or different goals than the design people and we usually don’t talk publically to sales people. I’m like “I don’t know. You should put this in your bag.” Sales people, they’re always following – normally, they’re always following the trend that just happened whereas as designers we’re always trying to design something new that hasn’t happened yet so you’re always pushing against the sales people that they’re going from an idea that they can say “Oh, that sold so well this last year so we should do that this coming year.” And we’re like “We need to be leaders, not followers.” And this is such a better idea but if it hasn’t been proven to sell it’s really hard for the sales people. They have to see that proof within the sales. So you always have that hard thing to deal with with sales people as they have that fear of “How am I going to sell that? I don’t even know if that’s a good idea.” Us designers, we have that mentality of “It’s a great idea. It’ll do great.” They want proof. Unfortunately we run into that it seems like all the time with the sales people and the design departments.

That’s a really good point. With that said though, the last few years you’ve had Tae from Boreas and Benji from Poler and his group and a lot of these new and younger upcoming brands that I know…

Trisha: Tae is a huge influence. There’s so many times that you hear “Oh, I love that brand’s packs.” I want that clean style.

Do you think it’s influenced new opportunities because people are trying to change and you have this – OR, there’s this very clear disconnection between the older guard versus the younger guard and that younger guard is shaking up that older guard.

Sky: Absolutely.

And you could see that it’s making people feel a little bit unsteady while the younger guard is going in there and they could care less and they’re not – they’re just young just like we were all young.

Sky: Yeah. It’s very refreshing.

Trisha: Tae has the right sort of personality or sales type that I feel like he is one of those really foundational companies that is helping people like the old guard think “Okay. The new guard’s not so bad.” You have people like him. Maybe it’s Tae’s personality but it’s his designs too where he’s somehow able to bring that together and I think it’s helping everybody accept the new ways better.

Sky: And I think it really comes back to kind of what I was talking to earlier about people’s relationship with the product and Tae takes it another step forward to people’s relationship with the outdoors as a concept and he’s really – I feel like it’s his mission to enable that interface to happen. Then he started the lending library for gear down there and I think that that’s the way to think about it, whereas the old guard thinks about “We want to sell product.” But it’s more of a relationship between a customer and not just the product but the whole idea of being in the outdoors or recreating or whatever that is. It’s changing and it’s really refreshing and it’s great to see people coming at it from a different angle. Tae is a mentor. You interact with him and he’s so open, he’s so willing to share his experiences and his knowledge with anybody who asks him. He’s not one of these guys who’s like “Oh, my ideas are cool and I’m going to keep them over here.” It’s like “Hey, my ideas are cool and let’s get them out there.”

Trisha: Yeah. I think it’s people like him who are getting those two sides to find a middle ground and then they see the sales and they see – but it’s a truly different world. We’re already getting old school. We’re already feeling kind of old and the whole new outdoor market is – that’s really like lifestyles, car camping. We still backpack and we’re some of the few people we know between 40 and 45 who backpack. Most of our friends say “Why would you do that? It’s painful and it’s so boring.”

And we go out and we don’t see anybody. We’re not even going out far and you’ll see people on motorcycles, mountain bikes, maybe day hiking but backpacking, you hardly see any. We are in Montana but we just don’t see people backpacking that much which is great for us because we’re alone and it’s awesome but it’s not that old style business. You have to sell into something that people have multiple uses for.

That’s awesome. Thank you.

Trisha: Thank you.

Sky: Thanks!

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews