From Concept to Production :: The Story of the Tortuga Daypack

Hey, I’m Fred Perrotta, the co-founder of Tortuga Backpacks. We make carry-on-sized, urban travel backpacks, which have twice made the finals of the Carry Awards (but I’m not bragging, ha!). When we started our company in 2009, I had zero knowledge of product design, engineering, or manufacturing. And since, I’ve learnt a bunch. And wanted to give back a little.

Hopefully by dishing up the A to Z of the production of our newest offering I can help prospective entrepreneurs bring their carry ideas to market.

You know, I wish I had this kind of information when I started!

If you want more insight into this or another step in the process, I’m happy to oblige, just ask away in the comments.

So here goes…

The Niche Came First

I was working from the road and had no way to carry my clunky old laptop from my Airbnb apartment to a cafe.

Since I was traveling, I didn’t want to work from the apartment all day. Carrying a second bag for my laptop wasn’t the right answer either. Multiple bags are anathema to the light travel, one bag lifestyle I advocate.

Asking around led me to daypacks. Lightweight, packable daypacks are easy to bring along without adding a second bag. One friend’s advice led me to the Marmot Kompressor. The Kompressor and its competitors were fine but not quite right, especially for urban travel. Most felt like an afterthought by the outdoor companies that made them.

The existing bags were made by hiking companies and weren’t quite right for travel. Brands were optimizing products for the wrong features. The market had no clear winner. The problem and opportunity were clear. The solution was not.

“Brands were optimizing products for the wrong features.”

Identifying the Problem

After testing the available options, their shortcomings were clear.

The makers of packable daypacks were trying to make the lightest possible bags. This is the feature they optimized toward and promoted in their marketing.

That’s fine for certain hikes where every ounce counts. In most cases, including travel, utility is paramount. Who cares how much a bag weighs if it doesn’t make your carry easier? Even one ounce is too much if the bag is useless.

In the quest for lighter daypacks, brands were leaving out valuable features. No padding, so your back is a sweaty mess. No exterior pockets, convenience be damned. No organization, which is still a problem, even in a small pack.

To the drawing board!

“In most cases, including travel, utility is paramount.”

Research and Design

We always start new product development with a design brief.

Before we sketch anything, we outline the product’s mission and requirements. We meticulously map the competitive landscape to avoid duplicating what’s already on the market.

The mission for the daypack was to carry anything you would need for a day on the road.

The requirements were:

- Is packable

- Weighs less than 1 pound (0.45 kg)

- Holds 15 to 20 liters

- Has exterior (water bottle) pockets

- Has a top, zippered pocket for quick access

You can see the spreadsheet of existing products here.

Then we take the design brief with requirements and market research to our industrial designer. Listen to this interview for more on finding and working with an industrial designer.

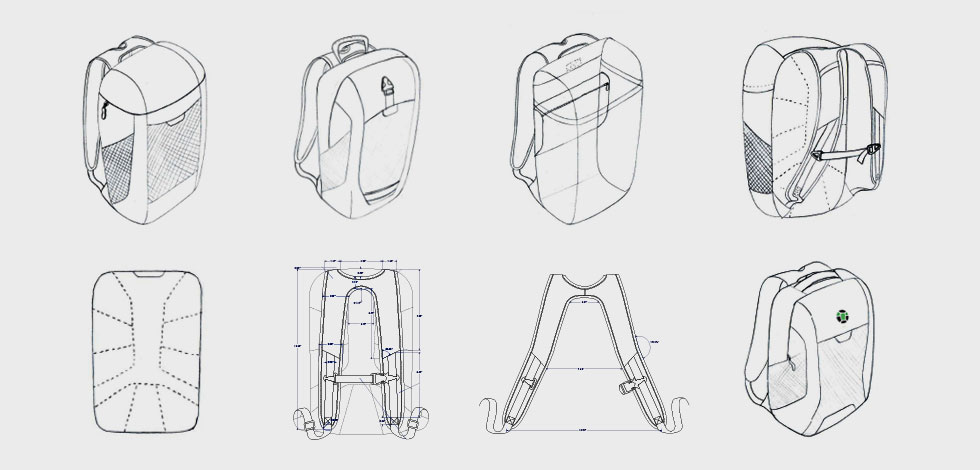

Our designer works from the brief to sketch out a few initial concepts. Each concept is a different construction, look, and combination of features.

“Before we sketch anything, we outline the product’s mission and requirements. We meticulously map the competitive landscape to avoid duplicating what’s already on the market.”

From the initial concepts, we choose one to serve as the base design then incorporate features and design cues from the other concepts as needed.

After another round of refinements, the designer turns those sketches into a tech pack for our supplier.

The tech pack is like a blueprint for soft goods. The document outlines the lengths and angles of the backpack, the hardware and fabrics used, and the construction techniques needed to make each feature work correctly.

Next, we move on to sampling. Our supplier builds a sample from the tech pack. We test it and make notes. Then we send those notes with plenty of pictures to the supplier for the next sample.

We usually go through three to six samples to get to the “production sample”. This final sample is the version of the product which the supplier will use for mass production and which we will use for comparison during quality control.

A note on suppliers: Finding and choosing a supplier is another topic outside of the scope of this post, but I wanted to provide some direction. To find a US supplier, start with ThomasNet or Maker’s Row. Alibaba is the top site for sourcing in China. The Enter China community can also help connect you with suppliers and sourcing agents. Ask for referrals, and do the real work in person. Don’t expect much from any suppliers that you haven’t paid or met in person yet. Give them a reason to care about your business.

“Don’t expect much from any suppliers that you haven’t paid or met in person yet. Give them a reason to care about your business.”

Troubleshooting Samples

Problems with samples typically fall into one of three buckets:

- Mistakes you caused the supplier to make

- Problems not anticipated by the tech pack

- Changes needed based on testing

Let’s look at an example of each that we encountered in the sampling process for the daypack.

Mistakes You Caused the Supplier to Make

The supplier may have made the mistake, but the mistake is your fault. Discrepancies between what you wanted and what you got are due to missing or vague explanations in the spec. You should make all of the decisions. Anything left up to interpretation can be interpreted incorrectly. Don’t leave any room for error.

“You should make all of the decisions. Anything left up to interpretation can be interpreted incorrectly. Don’t leave any room for error.”

In our case, we had to subtract padding and stiffeners through the first few samples. Our previous backpacks have been heavily padded. Now we were asking the supplier to strip away most of the padding.

Explaining the end result that you want can answer design and construction questions. Clearly articulating your end goal will help your supplier bridge the gap between your spec and what you want in the final product.

For example, we explained that the padding had to be minimal enough for the daypack to pack into its own top pocket. Describing this outcome supplements specs like the thickness of foam in millimeters.

“Clearly articulating your end goal will help your supplier bridge the gap between your spec and what you want in the final product.”

Problems Not Anticipated by the Tech Pack

If you’ve never designed a product before, this is an easy category to overlook.

Just because something worked on paper does not mean it will work in real life. Good designers anticipate these problems and avoid most of them. However, a few issues are unavoidable.

“Just because something worked on paper does not mean it will work in real life.”

In our case, the front pocket and handle had to be redesigned. When you pack a bag its shape changes, regardless of what was drawn on the spec or what was cut and sewn. When we packed the first samples, the front mesh pocket curved under the bag. The pocket was in contact with the ground and in danger of ripping. The front handle was underneath the bag and completely useless for picking it up.

We also found that a rain flap would not work in the ripstop nylon body fabric that we intended to use. The fabric was just too thin and kept catching in the zipper pull.

As soon as you have a sample, the spec goes out the window. From then on, you’re working from a real, physical object. You can update the spec later, but the sample is now your point of reference.

Changes Needed Based on Testing

A related category of problems stems from materials and hardware. Even when using components that you’ve used before or have seen on other products, you’ll find that some don’t work well together. Or your supplier used the wrong fabric. Or the fabric you liked doesn’t feel right sewn into a final product. Or the hardware you chose just doesn’t work well.

We sent our supplier references to fabrics that we wanted to use. Usually we send a swatch from a fabric mill or another product that uses the fabric we want. This time, we sent two backpacks with fabrics that we liked for the mesh and for the body fabric. Even with sample fabrics you might need a round or two of revisions to get it right.

“Even with sample fabrics you might need a round or two of revisions to get it right.”

Delivering Feedback to Your Supplier

Communicating with suppliers can make or break new producers, especially when also navigating a language barrier.

We manufacture our products in China and have spent five years learning how to work with suppliers. Collaboration is a never-ending process.

Reviewing samples in person is best for asking questions and for discussing options. I prefer to talk about a new sample in person to discuss obvious problem spots or even to get changes made on the spot.

“Reviewing samples in person is best for asking questions and for discussing options.”

Then I take the sample with me, test it in real-world situations, and get feedback from our team and beta testers.

When I have all of my notes ready, I type them up with detailed instructions and bolded text for emphasis. Text is helpful, but pictures are the best way to communicate changes.

My sample notes are full of pictures with arrows and explanations and sometimes links to other products to show how we want something to work. For these notes, I use Skitch, which makes adding text and arrows for annotation easy. This email or doc will be your record. Then you can discuss the notes in person to elaborate. Plus, you’ll have them as a double-check when the next sample is ready. Did the supplier miss anything? Did a change get implemented incorrectly? Having this document is an important fallback and record. The notes will prevent you from forgetting anything. Always have a record of these notes.

“My sample notes are full of pictures with arrows and explanations and sometimes links to other products to show how we want something to work.”

Heading Into Production

Once you have a finished sample, you will approve it for production and place your order. An extra production sample can also be used as a quality control (QC) sample to confirm that the production version of your product is what you ordered.

I hope this post adequately explained the ideation, design, and sampling process behind soft goods. Aspiring makers can use it as a blueprint when getting started. I wish I had had anything when we were getting started. Instead, we learned everything above through years of trial and error. If you have any questions, ask in the comments and I’ll answer them.

The Tortuga Daypack described above is now available for pre-sale. Use the discount code CARRYO for 10% off your order through 3/18/15.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews