5 Key Elements :: Designing the Arc’teryx Voltair Avalanche Airbag

Arc’teryx is one of the most respected names in the outdoor industry, with a reputation for advancing design and always searching for better. So when they announced the new Arc’teryx Voltair Avalanche Airbag, the industry sat up and took note. While Arc’teryx Senior Hardgoods Designer Peter Hill handled the design of the pack itself, the mechanics of the airbag system were steered to success by the experienced hand of Gordon Rose, Senior Industrial Designer at Arc’teryx. We asked Gordon to share his insights on 5 key elements in designing the mechanics of the Voltair…

Multiple Deployments

Around ten years ago we looked really seriously at doing an avalanche pack. We wanted to do it for a bunch of reasons, because we didn’t like the pack designs. But after a couple of years of R&D and testing with compressed air, we figured we just couldn’t really overcome some of the shortcomings of that system.

The biggest one was the single shot deployment, and that was really because people couldn’t and didn’t train with them. So there were a lot of incidents where people weren’t successfully triggering their packs in avalanches even if they had it. Also there were a lot of accidental deployments where people would be on a trip and accidentally trigger it, and then their pack was out of commission for the trip.

“…there were a lot of incidents where people weren’t successfully triggering their packs in avalanches even if they had it.”

Another problem was if you deployed it in an avalanche, or your group got caught in an avalanche and people blew off their balloons and your cylinders were all cooked, and you’re out in the middle of 100% avalanche risk terrain and unable to get a second inflation. So we saw that as the biggest shortcoming.

Then in 2010 we hit on the idea of using an electric blower with a rechargeable battery. As soon as we did the very first test, we saw the kind of energy and we figured we’d be able to harness it, we knew we’d totally shift the whole paradigm. We could provide a system that you could recharge, get multiple deployments from and train with, use in an emergency, be able to reuse multiple times on one trip – all that kind of stuff. So that was probably the number one important factor.

Blower Style

The second key element was the blower style. We realized right out of the gate that having good pressure was going to be quite important. The big advantage that compressed air systems have is that when you first trigger them, they have a huge amount of pressure so they can deploy the balloon no matter what. They can’t keep filling it up though. If something goes wrong, once the shot is gone, it’s gone. But they have a lot of pressure.

So I first started looking at ducted fans from hobby shops. They’re used in remote control airplanes. It’s basically an airplane propeller in a tube. It’s just an airfoil and it spins and creates lift. Within the first six weeks of the project with the testing looking at static pressure and the physical strength of those systems, we moved away from that and decided it wasn’t going to be adequate. We broke a lot of them right away and weren’t able to get the pressures we wanted. They just didn’t generate enough static pressure to really convincingly pump the balloon out under adverse conditions, against the resistance of snow if you were falling or in an avalanche, or against frozen zippers and all that kind of stuff.

“The big advantage that compressed air systems have is that when you first trigger them, they have a huge amount of pressure so they can deploy the balloon no matter what. They can’t keep filling it up though.”

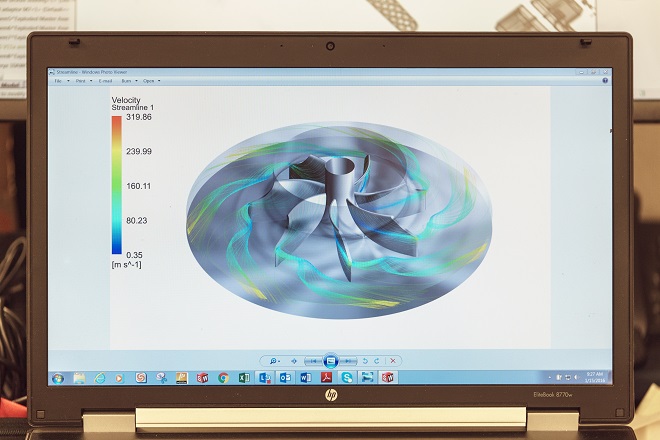

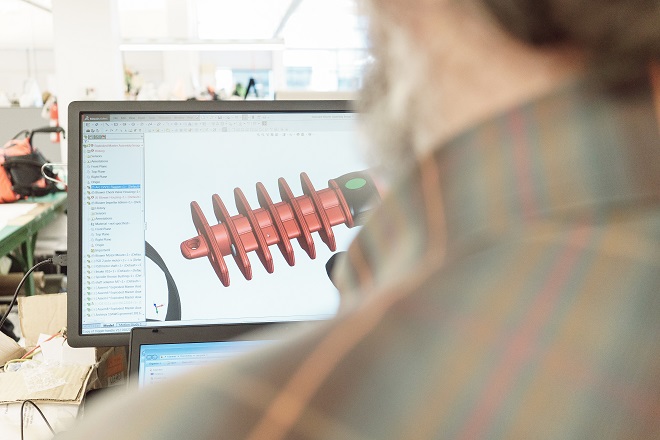

So then I started really searching and refining different kinds of blower systems for moving air. We ended up with a centrifugal blower, which is more like something that would be in a leaf blower or a vacuum cleaner. The vacuums use it to create suction, but it’s the same mechanics. You have a lot more ability to tune those between the amount of pressure that you want, or the amount of suction you want.

We also wanted a lot of very aggressive suction to draw air in, if it’s obstructed on the intake. It’s the same thing as pressure on the output. So, we wanted a very aggressive system for collecting air and blowing up the balloon with this. And with a centrifugal blower, you can pick your balance point between air flow and pressure rise, and really customize the curve and performance of that system to optimize it.

“We could provide a system that you could recharge, get multiple deployments from and train with, use in an emergency, be able to reuse multiple times on one trip…”

Once the balloon is inflated you want pretty good pressure, but the big one is to get the thing going. We really optimized that centrifugal blower, so we get really good static pressure but we also get really good air volume. If you punch a hole in it, it keeps pumping for a minute. You can pull a trigger at any time and keep it going indefinitely, really, if you have to. So that was kind of part and parcel of having an electric blower, so you could keep using it, but really to optimize the centrifugal blower so that we could get a tailored balance between pressure and air volume.

Battery Development

The third element was the battery development itself. I knew right out of the gate I’d be using a brushless DC motor just because of the torque and power those things can deliver, but to get performance at -30 degrees Celsius, where we wanted a really large amount of power. With the centrifugal blower it was about being able to transfer more energy to the air. If you’re getting less pressure, less volume, then you’re actually not putting as much energy into the air. So with the blower, we had a physical means to actually put a lot of energy into the air.

However, we needed a power source that was going to be able to supply that energy to the motor, so it was crucial to have a battery that could put out super high currents at really low temperatures. It took a lot of work to come up with a 100% custom lithium polymer battery system.

“We really optimized that centrifugal blower, so we get really good static pressure but we also get really good air volume.”

There’s firmware for driving the motor and the battery. That’s kind of the brain of the system, the whole electronics of it. The whole energy delivery system would be the battery combined with the controller and everything to get that powered and motored. So that’s all 100% custom – the motor, both the battery and the software driving the motor, and all the data logging and everything that’s in there. Even the data collection opportunities are going to move avalanche balloon bag knowledge forward in general. So that’s all tied in together to that electronics package.

The firmware does control the whole thing. But basically, what we did through five years of testing is every time we found a failure around the electronics or the driver, we did a hardware fix on the electronics, and a firmware fix on the electronics. So basically, there are things like if you suddenly cut power to the motor, it keeps spinning and generates a bunch of electricity that shoots backwards into your circuit board, and you can control that with firmware. But if something is wrong with your firmware, a lot of the time it will overload the electronic components on the motor controller, and burn things out and create failures in the hardware.

So we actually built the hardware to withstand those kinds of power surges, and we did the firmware to prevent them from happening in the first place. We looked for hardware and firmware redundancy every step that we could, taking that approach rather than just relying on a firmware fix. Reliability was crucial.

“…it was crucial to have a battery that could put out super high currents at really low temperatures. It took a lot of work to come up with a 100% custom lithium polymer battery system.”

Trigger Mechanism

The other thing we were really unhappy with on other backpacks that were already on the market was the triggering device. A lot of people would have accidental triggerings, or they wouldn’t be able to trigger. Part of it was training, and part of it was that the handles all zippered away or got covered in Velcro or were quite complex. I wanted to design a handle that was always available, that was really intuitive and tasked to lock and unlock.

So the whole trigger handle mechanism just spins 180 degrees to lock or unlock it; it’s always there, you don’t have to tuck it away. Even if you have it locked when you grab it to pull it, you can twist it and unlock in an emergency. But if you’re thrashing through some bush or something, you can lock it so you don’t accidentally trigger it. It’s a really unique shape, so that when you grab it, you actually know that’s what it is. That was one of the big design things that we wanted to address in general. That would apply equally to air-powered packs and electric-powered packs.

We went through a ton of handles, and we looked at fully electronic switching. Like, you could do a button on your ski pole that transmitted to the pack. Basically, all the really cool electronic things and electrical switches on the shoulder straps and all that kind of stuff. What we ended up finding was that eventually what failed was all the fancy electronic connections. So we went back in the opposite direction, where we wanted to keep that trigger mechanism as mechanical and simple and robust as we could, and keep all of the electronics really embedded inside of the backpack and protected from exposure and weather.

“I wanted to design a handle that was always available, that was really intuitive and tasked to lock and unlock.”

I went through a lot of iterations of handle shapes, trying to get something that was easy to grab but wouldn’t hang up on branches and get snagged by trees or hooked from your glove. Originally the handle had kind of like a gun lock system that split side to side to lock and unlock it, which worked really well. But in our field-testing we found that it was prone to getting iced up, which wouldn’t create an emergency, but it was inconvenient and delaying. The whole point of the thing was to make it really convenient and not annoying, so we scrapped that idea.

During that testing we came up with the idea of having sort of a camera style lock where as you turned it 180 degrees, it locked and unlocked, which became this super intuitive thing that doesn’t freeze up and is easier to use and more intuitive to look at. So we switched to that and then we did a lot of different handle designs as well to come up with the right shape and position for different hand sizes, and to make it ambidextrous so that you could grab it with the right or the left hand. There’s some range of motion in that, so once you pull it you have a couple of inches of travel before it triggers the whole system. So that, again, is to prevent accidental triggering.

And then the other thing with the electric system is the battery on-off switch is super accessible. So we’ve got levels of redundancy in disabling the system. The simplest is just to lock the handle. But if you’re getting on a helicopter or a chairlift somewhere, and it’s important that the thing doesn’t go off accidentally, you can just open the little zipper and turn off the battery, which guarantees it can’t go off. The third level of redundancy is you can take the battery out for air transportation and that kind of thing.

“…we’ve got levels of redundancy in disabling the system.”

Leg Loops

The thing that really always bugged me about other packs was leg loops. Leg loops are important to the safety of the pack. We basically say if you’re not going to wear the leg loop, don’t bother wearing the pack. There has been some debate around that, but all the companies that make climbing equipment, like Arc’teryx and Mammut, that were actually doing avi packs also thought that the leg loop was crucial, because you want the weight transferring into that leg loop the same way it does in a climbing harness.

Unfortunately, two years ago someone up in Revelstoke BC died because they were wearing the avalanche pack, and they triggered it successfully, but they weren’t wearing the leg loop. So the balloon and pack actually ended up on the surface of the snow, and the person was down below with their arms pinned and they died because of that. It was tragic, and we really emphasize the importance of that. And it was the kind of thing where for 30 years of avalanche packs, everyone complained about it. But no one bothered to really try and make it better.

“Leg loops are important to the safety of the pack. We basically say if you’re not going to wear the leg loop, don’t bother wearing the pack.”

It was important to get the geometry of the leg loop defined properly so it transfers the weight properly, up into the backpack and up into the balloon so it’s actually supporting the user, but you’re not relying on the waist belt or anything like that. You actually have the structural webbing harness that holds you up and attached to the bag. Then I wanted a really intuitive, simple, fast one-handed motion for latching and unlatching it. So I got inspired by ice clippers, which are kind of like a carabiner but they’re a big plastic loop that ice climbers use to rack up ice screens on so that they can single-handedly pop them in and out while they’re climbing. I had the idea to make one of those, but super miniaturized and structural as the connector, and then mount it to the hip belt to stabilize it. So I played around with that and came up with the version that we’ve launched. It actually makes the leg loop intuitive and really easy to click in and out with one hand.

The aim was to make it convenient enough that people didn’t try and avoid using it, and you can actually swing the backpack off without undoing the leg loop. So if you need to get your shovel or probe out during a rescue, or even getting on a chairlift, you can swing the pack around to your front and access it without ever undoing the leg loop, which is really important if you happen to get caught in a slide while you’re trying to get your shovel out or something like that. At least you’re still tethered to your pack a bit better.

“…you can actually swing the backpack off without undoing the leg loop.”

Those are the five key elements for me…

Editor’s Note: we were kinda interested about the balloon too, so we pushed Gordon for a 6th Element – we just couldn’t help ourselves. 🙂

The shape of the balloon aims to balance protection and unobtrusiveness. There tends to be in Canada more injuries and fatalities in avalanches from contact with objects like trees. We have a lot of tree skiing here. In Europe, they tend to have more peaks and open bowls and stuff, and in BC we tend to have a lot more trees. You see people getting injured just from impact during the avalanches. So we wanted to try and produce a balloon that gave some protection up around the head and neck. There’s not actually any data on that, so we’re not really claiming any specific performance benefit there. But we had one guy in our office in an avalanche go over a small cliff and land on his head with the balloon inflated, and he was glad to have that shape up and around his head.

Some of the balloon shapes, like Mammut’s Snowpulse, were trying to make balloons that really encased the head and neck for protection. We wanted one that had less interference when you were skiing, but also had an orientation towards the head, in a definitely head-up position. We wanted as much protection as we could get up around the head and neck position, but still have it 100% unobtrusive when you’re skiing with it. And when you are skiing with the balloon deployed, you have to really look around to even see the balloon. A lot of the guides and snow professionals we deal with were really concerned because they didn’t want their ability to ski out of an avalanche to be hampered by the balloon. So that was the reason it doesn’t have more up around the head.

UPDATE : IF YOU’VE PURCHASED THE VOLTAIR PLEASE READ THIS ADVISORY NOTICE (DEC 6TH, 2017)

* Photography by Brian Park

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews